The Khan Valley

25 October 2007

A camelthorn tree is a complex ecosytem. Lots of creatures survive in its bark and its seeds are protein rich; caviare to the desert elephants. No elephants here though.

I’m in the Khan valley. Found a perfect camping spot up a side valley to the south under a Camelthorn. 30km from anyone. The only sound is the occasional noise of an aeroplane and the very distant 10.30 rumble of the blasting in the Rossing pit 30 km upriver where the big boys are disembowelling the desert to satisfy the Chinese demand for Uranium. Over 10% of the world uranium comes from within 50 miles of where I’m sitting.

Otherwise its just me and the barking gekkos. Hottish days and cool fullmoon nights

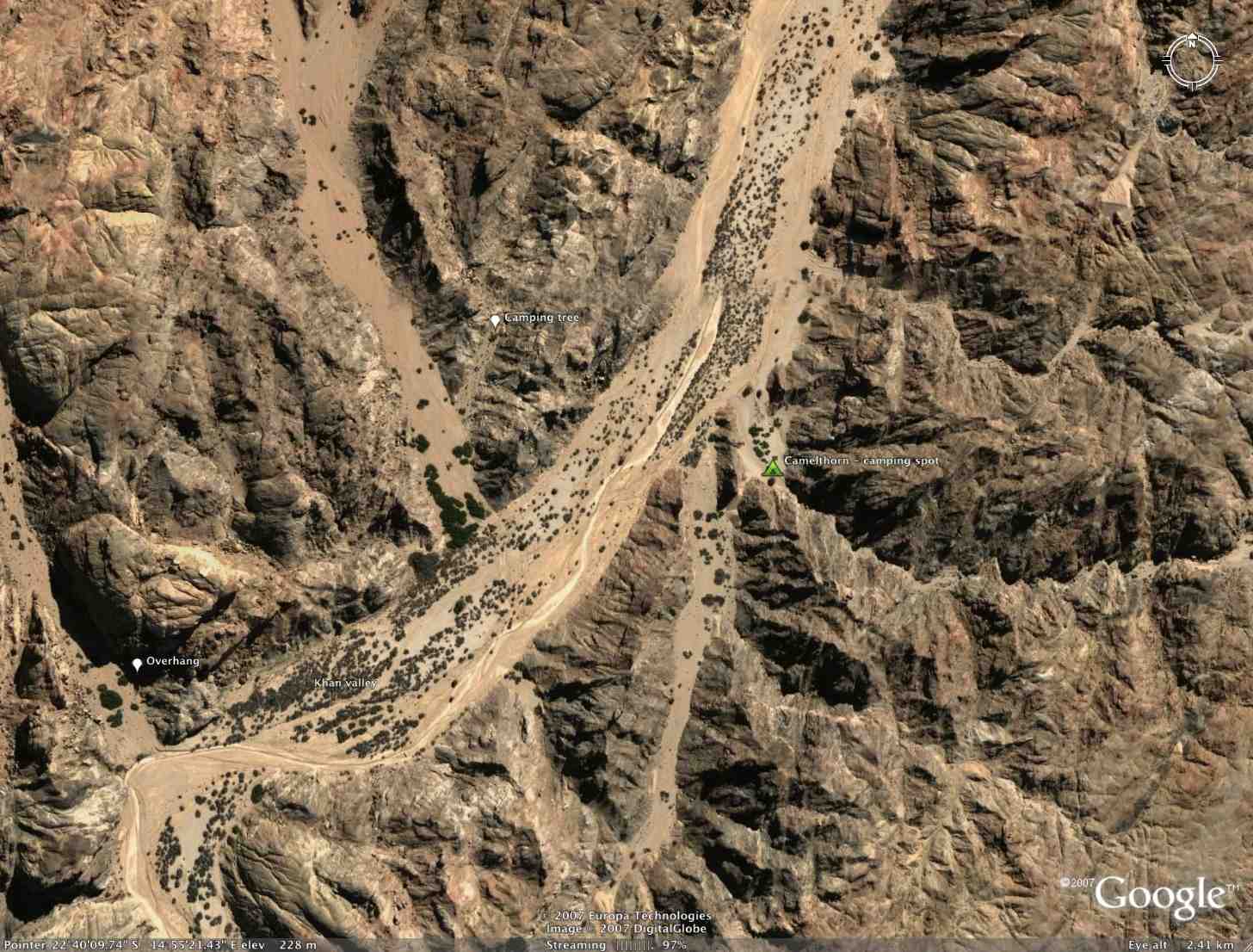

The Google Earth view of the area - the Camelthorn is just below the tent icon - shows the river. dry most of the time but now and then a spectacular torrent that washes all central Namibia's hard-won soil into the south Allantic. The flood can be 4m deep and cross the whole valley and washes away everything, including, quite often, the bridge at Usakos, about 50km upstream from here.

It's been doing it for millions of years and gouged out this 250m deep ravine through a granite plateau, down which I drove to get here.

Interestingly there is just one track; the desert ecosystem is delicate and the strict rule is no off-track driving. Much of the desert surface is held together by a complex mixture of adapted microorganisms and car tracks disrupt this making it open to erosion and damage that is irreparable (some ox-wagon tracks of 150 years ago can still be seen here and there). But this rule is not strictly necessary in a river bed which will be re-made every few years. Nevertheless the few people who come down here obey it. Not only that, they always leave their camping places as they found them; there is not a trace of litter.

I passed a small herd of springbok. They took no notice of me. Gemsbok and Klipspringer are also common in the valley; there were plenty of recent spoor and dung but no sign of them. I saw one black backed jackal on its eveng stroll and also the spoor of a sizable cat, probably the African Wild Cat which is interesting as the books say it does not live in the desert. And of course, here and there, always impeccably placed for all-round viewing, baboon turds.

The way into the valley is via a track past the now derelict Khan mine some 25km upstream from my tree. For much of last century copper was mined there and a permanent community existed (its rubbish dump tells much about it, not least the huge number of brandy miniatures).

This casting is part of a machine used to break up the ore; it was cast at the Phoenix Foundry in Stalybridge, Lancashire, of Robert Broadbent and Son, who I think also made the rivets that (still) hold up the Eiffel Tower.

The Foundry is long closed; its site was recently home to the North of England Sausage Festival and an attempt on the world record for puppadum piling.

Sic transit...

I went for a walk in the afternoon today; there is a small opening in the rocks neat my tree and I squeezed through it. It opened into an ever-widening twisting valley - the one that curves right on Google - that astonishingly had water in it probably only yesterday as the sand was still wet. It led me up to the desert plateau.

I wondered around a bit, treading rock seldom, if

ever trodden by human feet, thinking occasionally that if I broke a leg

nobody would ever find me and 1 litre of Windhoek Finkenstein mineral

water would not last long in the heat. So I went down a different, but

similar looking valley a bit further upstream.

Where around a bend I had a surprise encounter with a very healthy looking Welwitchia, only the second I have ever seen in the Kahn. It was a female. It must have planted itself a few hundred years ago during a succession of good rains. It was covered in cones and in masses of the spotted beetle that occur nowhere except on Welwitchias (how did they find it). None of its seeds could possibly have been fertilised; she was doomed to live out her millennia as a maiden aunt, growing a couple of centimetres of new leaf now and then in a good year, respiring and photosynthesising immeasurably slowly . She will still be there, probably, long after the last human visits her.

Welwitchias have no known relative. They appear to be conifers. They grow two leaves only, a few centimetres longer in a good year. The leaves split and dry out at the ends. They have a long root to reach what water they can find. This is probably many centuries old.

The close-up of the 'cones' - far right - shows the large numbers of the spotty mealy bug that live on them. But you cant see them because, like most other things that live around here, they are so well camouflaged

A few long-dead camelthorns testified also to the good years in the distant past that might have seen her germination. They were obviously a century or two old when they died but how long ago that happened is anyone’s guess, they survive forever here.

I left her and headed down the valley for the Kahn. At the back of my mind I had begun to sense that I was not descending fast enough and so I was not entirely surprised when I came through a small gap and suddenly realised I was standing at the top of a 60m waterless cataract.

Back to the watershed to try again.

|

Anyone can forge swords into ploughshares but it takes the Afrikaners to turn ploughs into braai implements |

I'm hugely privileged to be able, still, to escape to natural places; places that in England since the fifties have increasingly been designated as 'unimproved' rather than natural and given over to motorways, reservoirs, forestry and other necessities to service the urban way of life. This is the kind of place most people now only see on television, the last gasping natural lung of a suffocating planet.

It wont last long; few of the educated governing elite in Namibia have ever seen, or would wish to see, a Welwitchia, or be able to name a Camelthorn, and a Springbok is something from the butcher's slab. Namibia is no different from anywhere else.